Initial Conditions

I am particularly interested in how the initial topography affects landscape evolution modeling. Typically for initial topographies, modelers start with a flat landscape and then add random, small topographic perturbations.

However, when you deliberately add structure (e.g., a small channel) to the initial topography, its signal is amplified and permanently retained in the landscape as a valley. We call this phenomenon, Extreme Memory. See for yourself; draw your own initial condition in Fig. 2! See more in Kwang and Parker (2019).

Instructions:

(1) Hold down the mouse and draw an initial channel.

(2) Move the mouse out of the box to run the model.

Experimental Landscapes

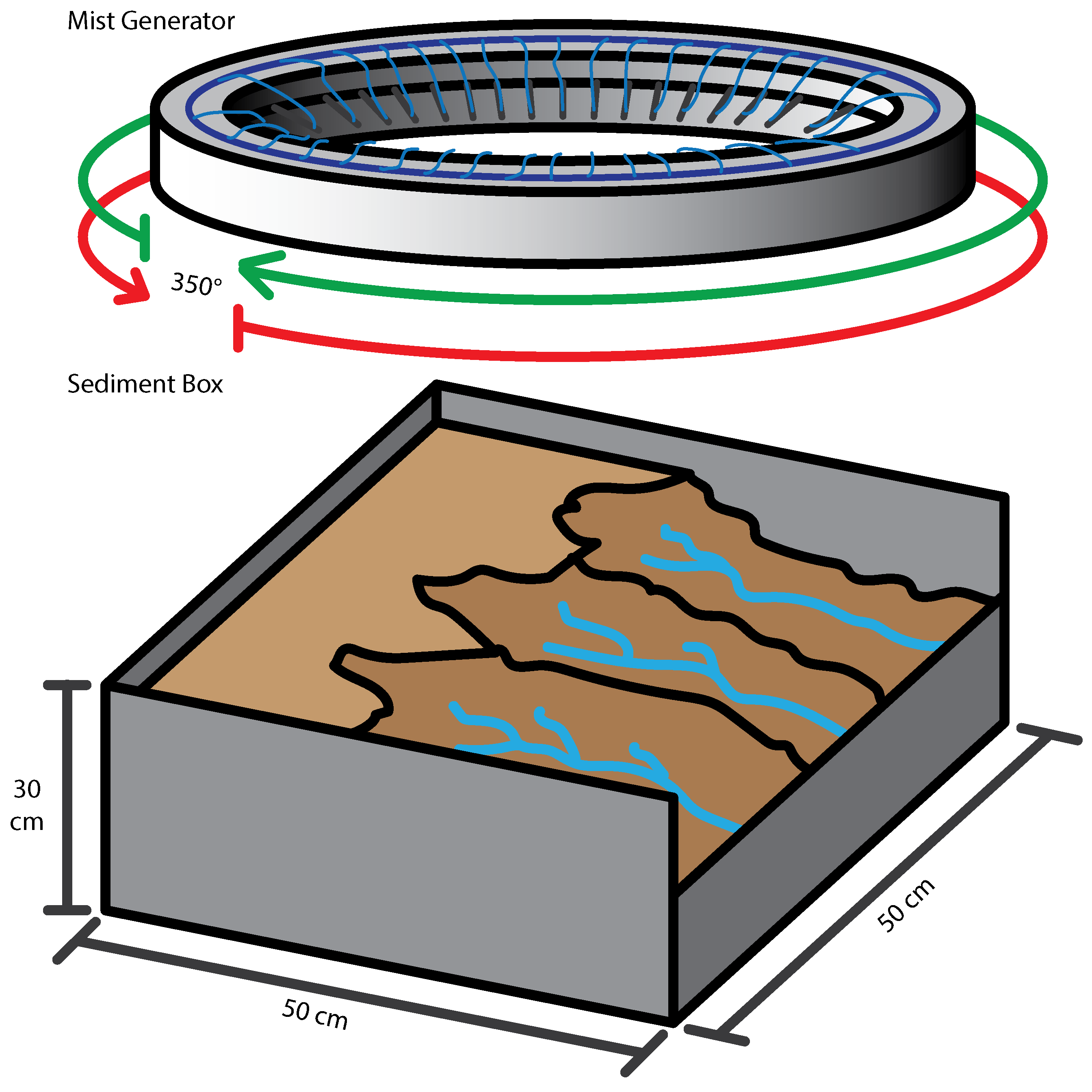

We also use small-scale experimental setups (Fig. 3) to study landscape evolution. Instead of rock, the substrate is made of a mixture of fine silica powder and water (and sometimes kaolinite). Instead of rain, precipitation comes in the form of mist. In these experiments, the substrate is either uplifted or the baselevel is lowered at a prescribed rate. Using this setup, mountains and valleys form within a matter of hours.

In our paper (Kwang and Parker, 2019), we drew initial channels in both numerical landscape evolution models (like Fig. 2) and physical experimental landscapes. While numerical landscapes evolved to retain signals of their initial conditions, experimental landscapes persistently reorganize to forget them. In our experiments, we observed lateral shifting of the channels that drove ridge migration, drainage capture, and stream capture.